One of our daily tasks is to clean out the cat litter boxes and we (on maybe I just wanted an excuse to automate part of the process!) run in to a couple of small problems:

- We usually don’t know if the other has already cleaned them.

- We obviously don’t want to forget.

- Since I primarily took over this job, I’ve been using a daily reminder, but it’s on my iPhone nagging me all day, even though it’s set for noon. I only need a reminder when it doesn’t get done.

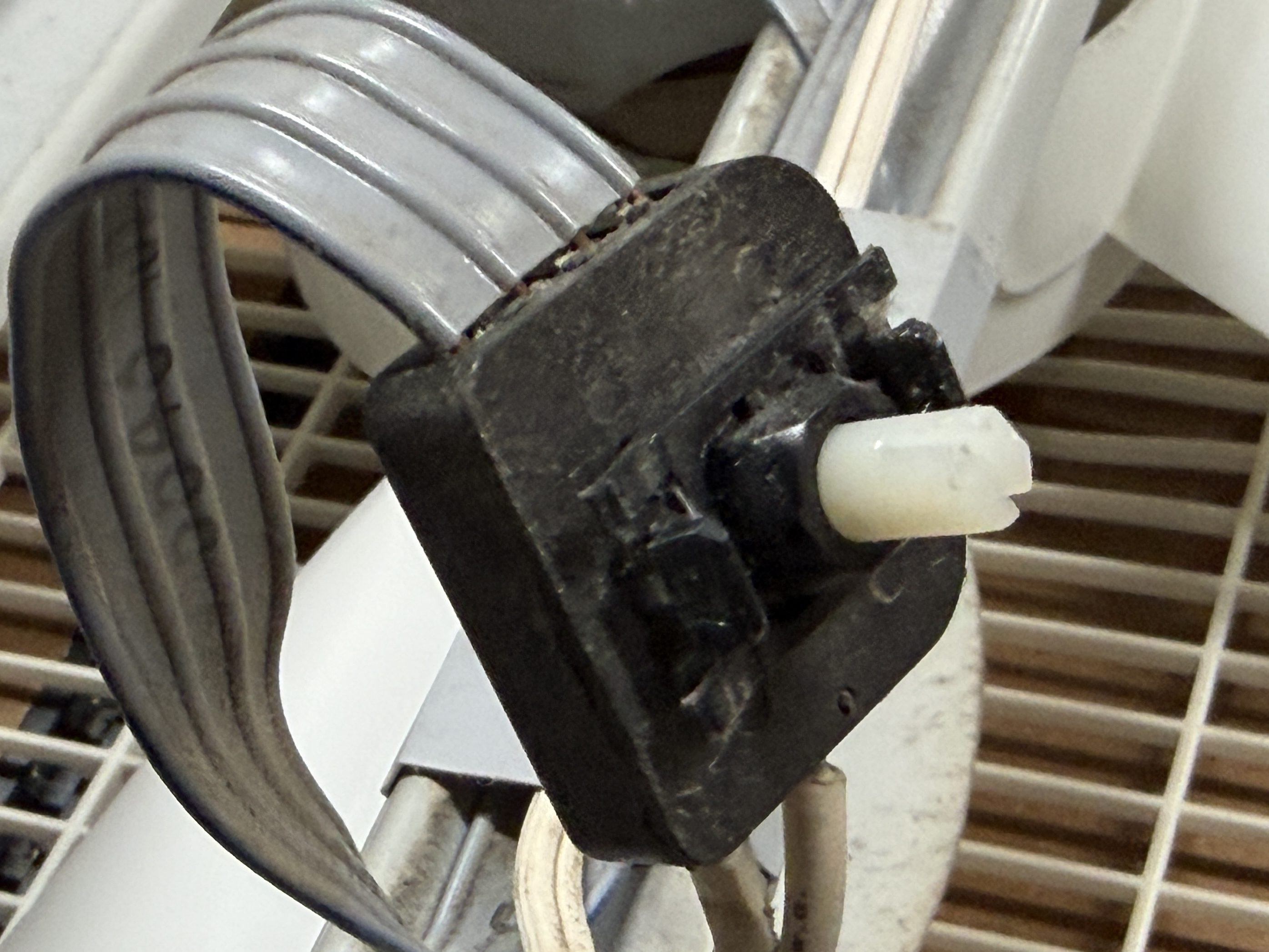

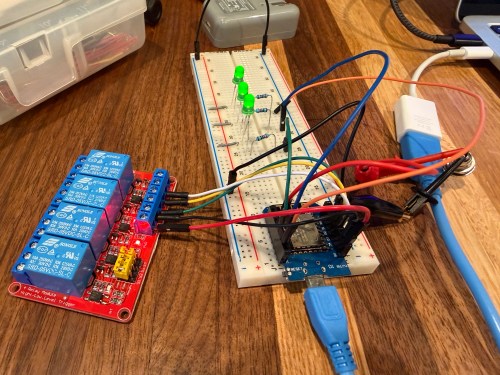

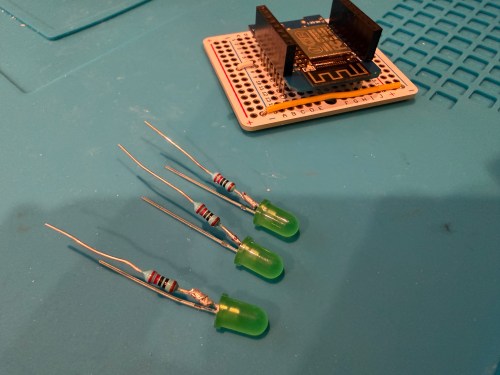

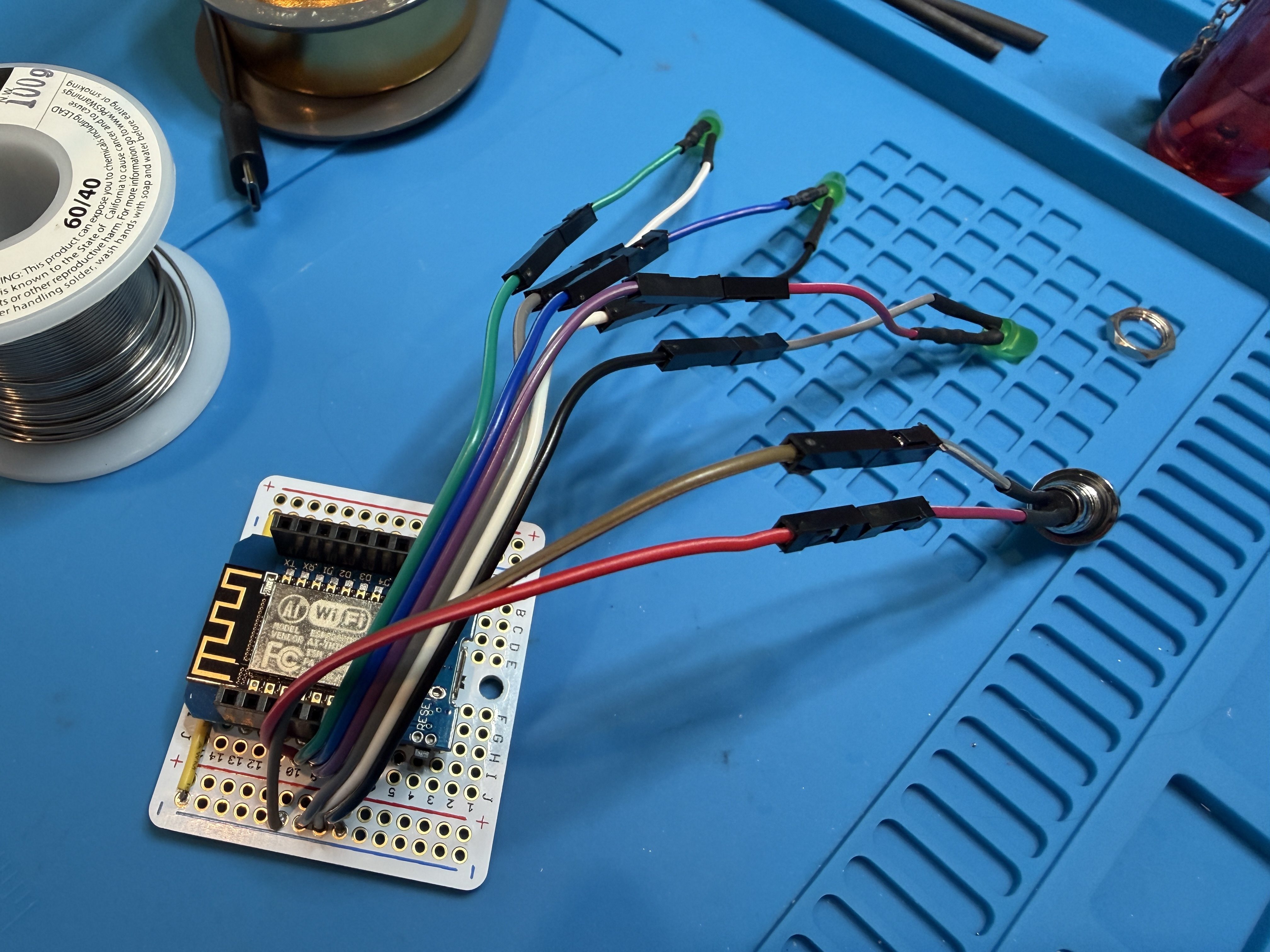

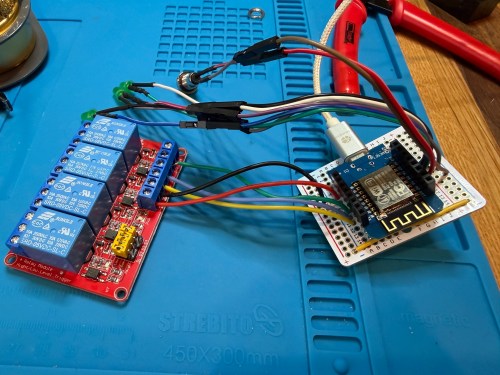

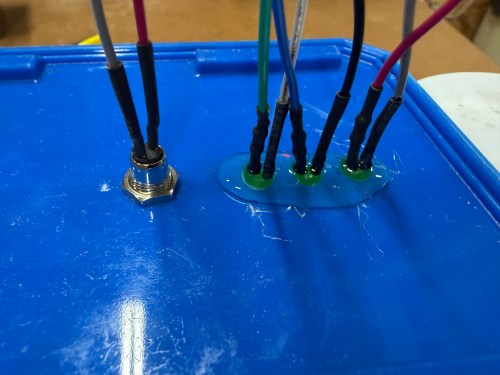

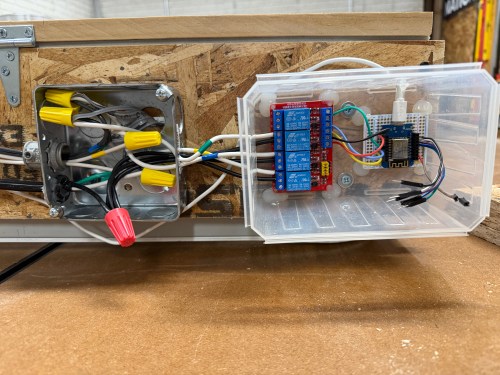

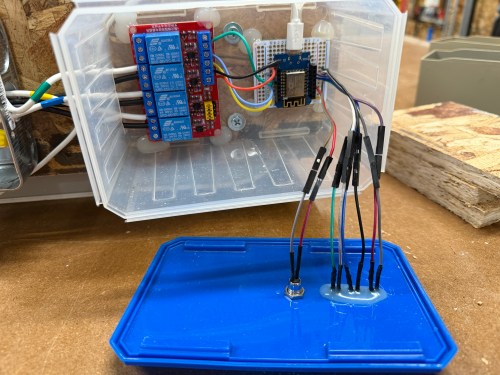

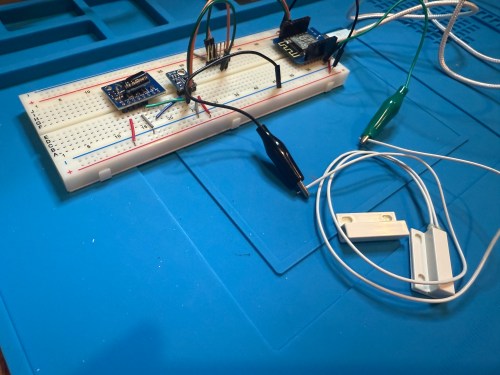

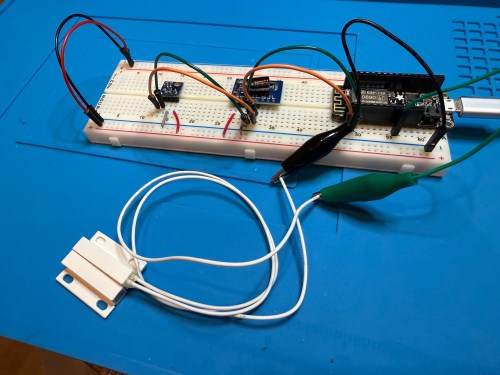

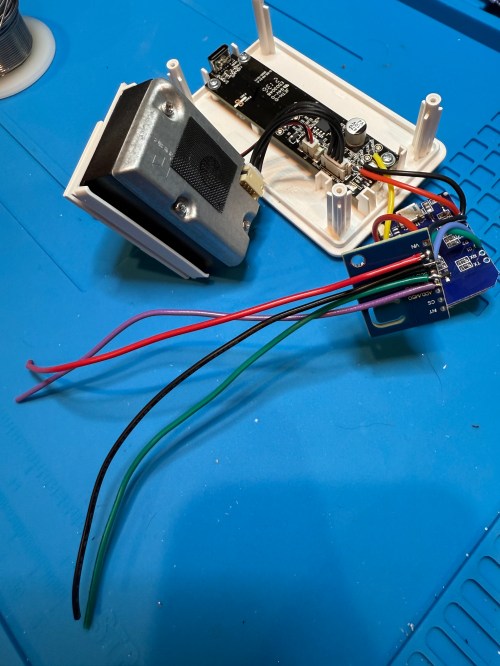

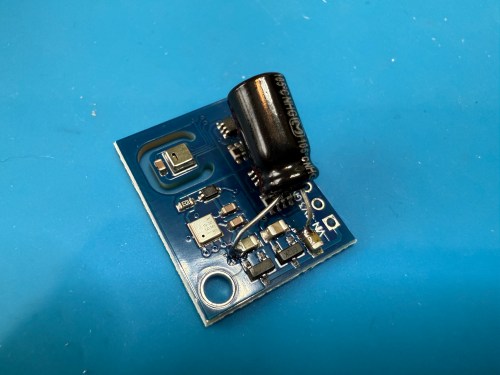

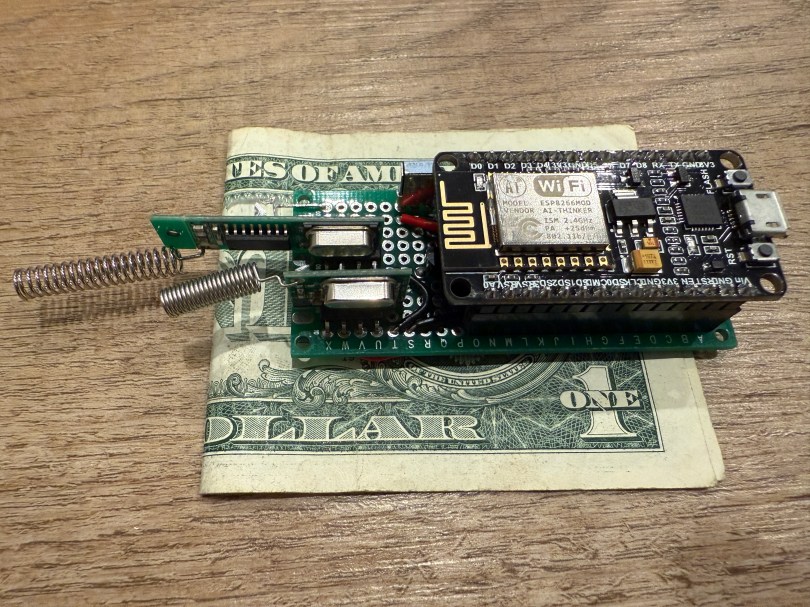

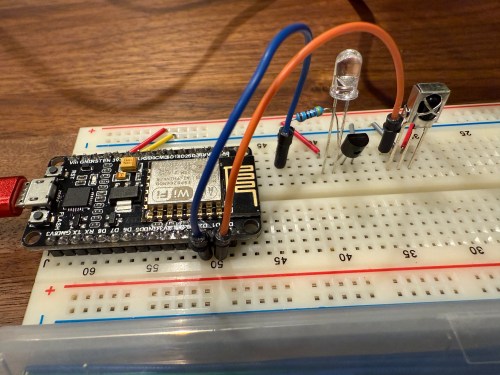

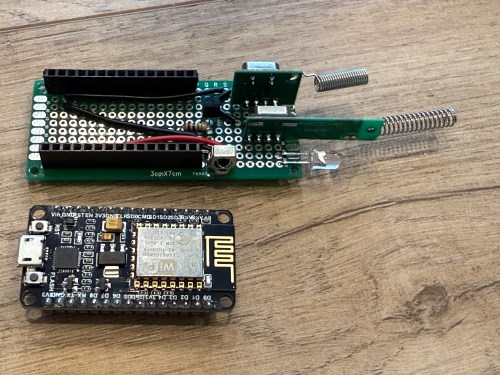

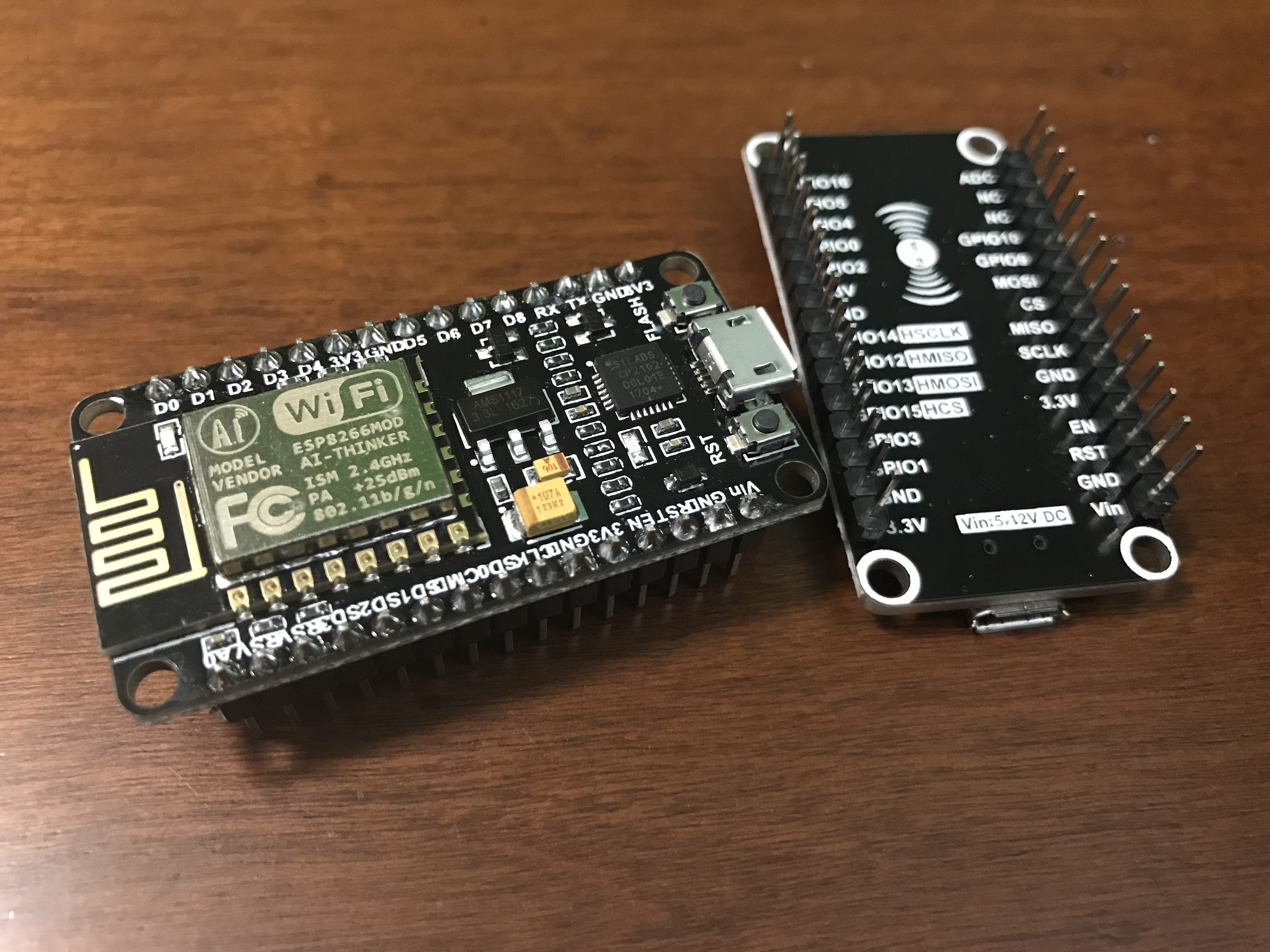

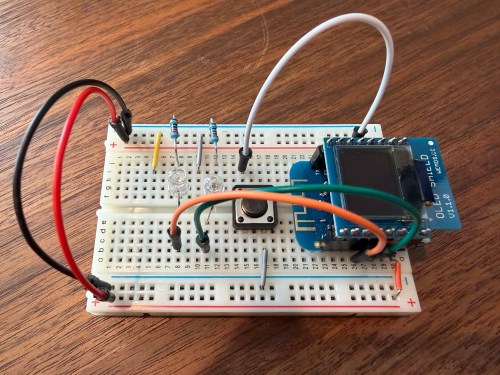

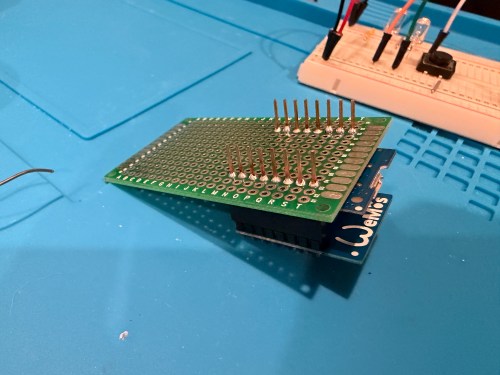

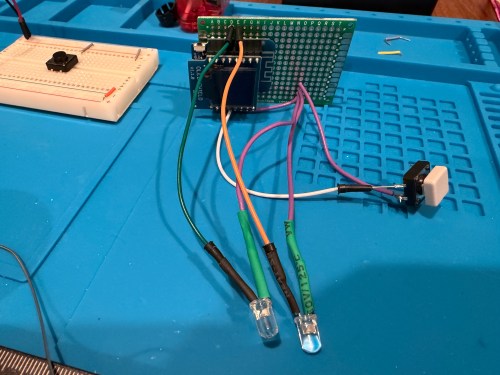

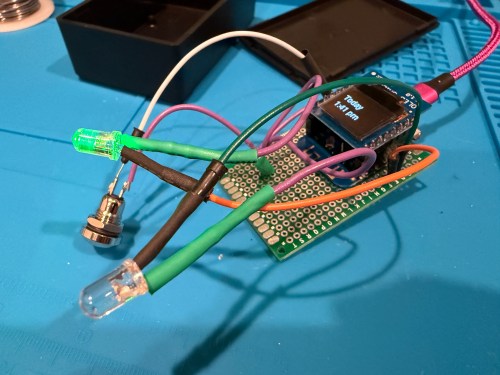

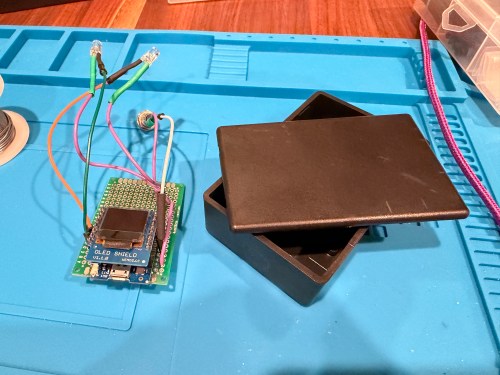

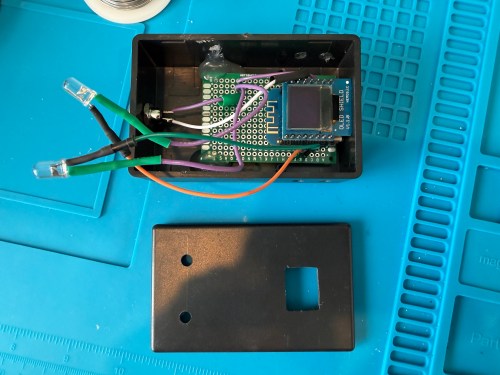

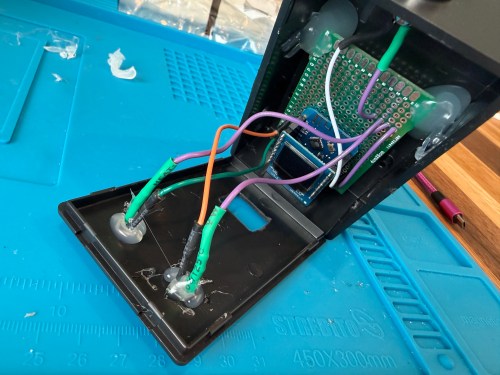

I thought of a solution with an ESPHome based device and Home Assistant. I used a WEMOS D1 Mini Lite, WEMOS OLED Shield, button, red LED, green LED, and 220 Ohm resistors. I connected everything on a breadboard for testing and then made it more permanent.

Key functionality:

- During the day, the green LED will be lit if the litter boxes have been cleaned and the red LED if they need to be cleaned. If we’re walking by, green means keep going and red means stop here.

- At night (8pm to 8am), the LEDs are off, unless the device is woken up.

- Press the button to turn on the display and status LED if at night. The display shows the last time the litter was cleaned in one of three formats, depending on how long it’s been.

- Today

1:23 PM - Yesterday

2:48 PM - 2 days ago

11:00 AM

- Today

- Press the button when the display is on to update the litter box last cleaned date and time. The LEDs flash to signify something is happening. The new date and time gets shown on the display.

- After 30 seconds the display turns off.

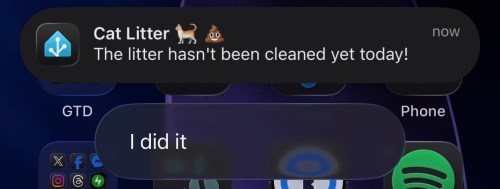

- At 4pm send a reminder to our phones if the litter boxes need to be cleaned.

- In Home Assistant a toggle can disable the reminders. Useful when we’re on vacation.

Here’s the ESPHome device YAML:

substitutions:

device_name: cat-litter

api_key: !secret catlitter_api

ota_password: !secret catlitter_ota

ip_address: !secret catlitter_ip

packages:

base: !include z_package_base.yaml

esphome:

name: ${device_name}

friendly_name: Cat Litter

on_boot:

priority: 800

then:

- lambda: |-

id(cat_litter_display).turn_on();

id(screen_is_active) = true;

- component.update: cat_litter_display

- script.execute: display_timer

esp8266:

board: d1_mini_lite

globals:

- id: screen_is_active

type: bool

restore_value: no

initial_value: 'true'

# WEMOS OLED Shield

i2c:

sda: GPIO4

scl: GPIO5

scan: true

id: bus_a

frequency: 100kHz

time:

- platform: homeassistant

id: esptime

on_time:

- seconds: 1

minutes: 0

hours: 8

then:

- script.execute: update_led_logic

- seconds: 1

minutes: 0

hours: 20

then:

- script.execute: update_led_logic

font:

- file: "fonts/Roboto-Regular.ttf"

id: roboto_font

size: 12

text_sensor:

- platform: homeassistant

id: litter_text

entity_id: sensor.cat_litter_status_formatted

on_value:

then:

- component.update: cat_litter_display

- script.execute: update_led_logic

binary_sensor:

- platform: homeassistant

id: remote_litter_status

entity_id: binary_sensor.litter_needs_cleaning

on_state:

then:

- script.execute: update_led_logic

# Physical button

- platform: gpio

pin:

number: GPIO0

inverted: true

mode: INPUT_PULLUP

name: "Cleaned Button"

filters:

- delayed_on: 50ms

on_press:

then:

- if:

condition:

lambda: 'return !id(screen_is_active);'

then:

# WAKE UP

- lambda: |-

id(cat_litter_display).turn_on();

id(screen_is_active) = true;

- component.update: cat_litter_display

- script.execute: update_led_logic

- script.execute: display_timer

else:

# TRIGGER CLEANED

- delay: 50ms

- homeassistant.service:

service: script.cat_litter_cleaned

- script.execute: led_flash_animation

- script.execute: display_timer

output:

- platform: esp8266_pwm

pin: GPIO14

id: led_green

- platform: esp8266_pwm

pin: GPIO12

id: led_red

script:

- id: update_led_logic

then:

- lambda: |-

if (!id(remote_litter_status).has_state()) return;

auto time = id(esptime).now();

bool is_night = false;

if (time.is_valid()) {

is_night = (time.hour >= 20 || time.hour < 8);

}

if (id(cat_litter_display).is_on()) { is_night = false; }

if (is_night) {

id(led_red).turn_off();

id(led_green).turn_off();

} else {

if (id(remote_litter_status).state) {

id(led_red).set_level(0.2);

id(led_green).turn_off();

} else {

id(led_red).turn_off();

id(led_green).set_level(0.2);

}

}

- id: display_timer

mode: restart

then:

- delay: 30s

- lambda: |-

id(cat_litter_display).turn_off();

id(screen_is_active) = false;

- script.execute: update_led_logic

- id: led_flash_animation

mode: restart

then:

- repeat:

count: 5

then:

- output.set_level: { id: led_green, level: 0.3 }

- output.turn_off: led_red

- delay: 150ms

- output.turn_off: led_green

- output.set_level: { id: led_red, level: 0.3 }

- delay: 150ms

- script.execute: update_led_logic

display:

- platform: ssd1306_i2c

id: cat_litter_display

model: "SSD1306 64x48"

address: 0x3C

rotation: 180°

lambda: |-

if (id(litter_text).has_state()) {

std::string full_text = id(litter_text).state;

size_t pos = full_text.find("@");

if (pos != std::string::npos) {

std::string day = full_text.substr(0, pos);

std::string time_str = full_text.substr(pos + 1);

it.printf(32, 8, id(font_main), TextAlign::TOP_CENTER, "%s", day.c_str());

it.printf(32, 26, id(font_main), TextAlign::TOP_CENTER, "%s", time_str.c_str());

} else {

it.printf(32, 24, id(font_main), TextAlign::CENTER, "%s", full_text.c_str());

}

} else {

it.printf(32, 24, id(font_main), TextAlign::CENTER, "Syncing...");

}

Some helpers in configuration.yaml:

template:

- binary_sensor:

- name: "Litter Needs Cleaning"

unique_id: litter_needs_cleaning

# This turns ON (Red LED) if the date is not today

state: >

{% set last = states('input_datetime.cat_litter_last_cleaned') | as_datetime %}

{% if last is none %} true {% else %}

{{ last.date() < now().date() }}

{% endif %}

- sensor:

- name: "Cat Litter Status Formatted"

unique_id: cat_litter_status_formatted

state: >

{% set last = states('input_datetime.cat_litter_last_cleaned') | as_datetime %}

{% if last is none %}

No Data @ --:--

{% else %}

{% set diff = (now().date() - last.date()).days %}

{% set time = last.strftime('%-I:%M %p').lower() %}

{% if diff == 0 %}

Today @ {{ time }}

{% elif diff == 1 %}

Yesterday @ {{ time }}

{% else %}

{{ diff }} days ago @ {{ time }}

{% endif %}

{% endif %}

notify:

- name: "momrik_phones"

platform: group

services:

- service: mobile_app_nick

- service: mobile_app_brandi

Automations in automations.yaml:

- id: '1768843528106'

alias: Notify - Cat Litter @ 4PM

description: ''

triggers:

- trigger: time

at: '16:00:00'

conditions:

- condition: state

entity_id: binary_sensor.litter_needs_cleaning

state:

- 'on'

- condition: state

entity_id: input_boolean.cat_litter_reminders

state:

- 'on'

actions:

- action: notify.momrik_phones

metadata: {}

data:

title: "Cat Litter \U0001F408 \U0001F4A9"

message: The litter hasn't been cleaned yet today!

data:

tag: cat-litter-alert

actions:

- action: MARK_LITTER_CLEANED

title: I did it

mode: single

- id: '1768843827814'

alias: Notify Clear - Cat litter

description: ''

triggers:

- trigger: event

event_type: mobile_app_notification_action

event_data:

action: MARK_LITTER_CLEANED

conditions: []

actions:

- action: script.cat_litter_cleaned

data: {}

- action: notify.momrik_phones

data:

message: clear_notification

data:

tag: cat-litter-alert

mode: single

One script in scripts.yaml:

cat_litter_cleaned:

alias: "Cat Litter Cleaned"

sequence:

- service: input_datetime.set_datetime

target:

entity_id: input_datetime.cat_litter_last_cleaned

data:

datetime: "{{ now().strftime('%Y-%m-%d %H:%M:%S') }}"

- service: notify.momrik_phones

data:

message: "clear_notification"

data:

tag: "cat-litter-alert"

I also added a couple of simpler helpers via Settings -> Devices & services -> Helpers:

- Cat Litter Last Cleaned – Date and time

- Cat Litter Reminders – Toggle

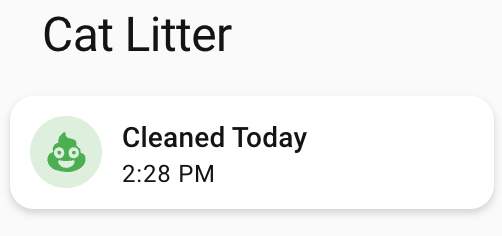

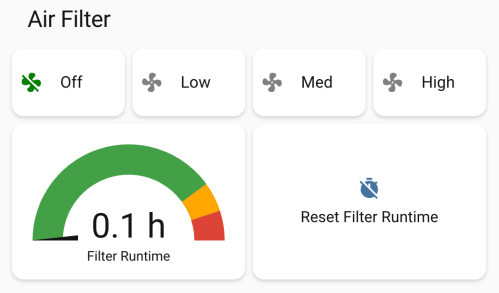

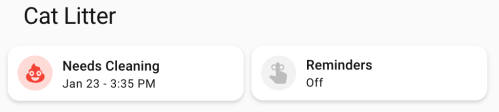

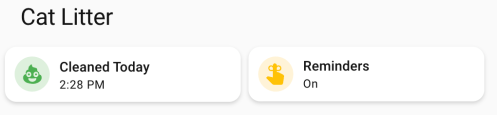

Finally, I added cards to a Home Assistant dashboard. See screenshots of the different states of each card below.

Here’s the dashboard YAML if you want it.

type: horizontal-stack

title: Cat Litter

cards:

- type: custom:mushroom-template-card

primary: >-

{% set last = states('input_datetime.cat_litter_last_cleaned') |

as_datetime %}

{% if last is none %}

Unknown State

{% else %}

{% set diff = (now().date() - last.date()).days %}

{% if diff == 0 %}

Cleaned Today

{% else %}

Needs Cleaning

{% endif %}

{% endif %}

icon: mdi:emoticon-poop

features_position: bottom

secondary: >-

{% set last = states('input_datetime.cat_litter_last_cleaned') |

as_datetime %}

{% if last is none %}

???

{% else %}

{% set diff = (now().date() - last.date()).days %}

{% if diff > 0 %}

{{ last.strftime('%b %-d') }} -

{% endif %}

{{ last.strftime('%-I:%M %p') }}

{% endif %}

color: |-

{% if is_state('binary_sensor.litter_needs_cleaning', 'on') %}

red

{% else %}

green

{% endif %}

tap_action:

action: more-info

icon_tap_action:

action: perform-action

perform_action: script.cat_litter_cleaned

target: {}

confirmation:

text: Are you sure you want to update the last cleaned date/time to now?

entity: input_datetime.cat_litter_last_cleaned

- type: custom:mushroom-entity-card

entity: input_boolean.cat_litter_reminders

name: Reminders

tap_action:

action: toggle

hold_action:

action: more-info

icon_color: amber

If we get a reminder, it looks like this. We can click I did it to update the date/time to now if we forgot to press the button on the physical device. With the automation set to run at 4pm, we should rarely see this though.

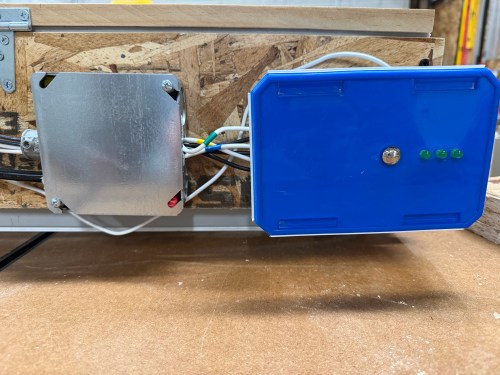

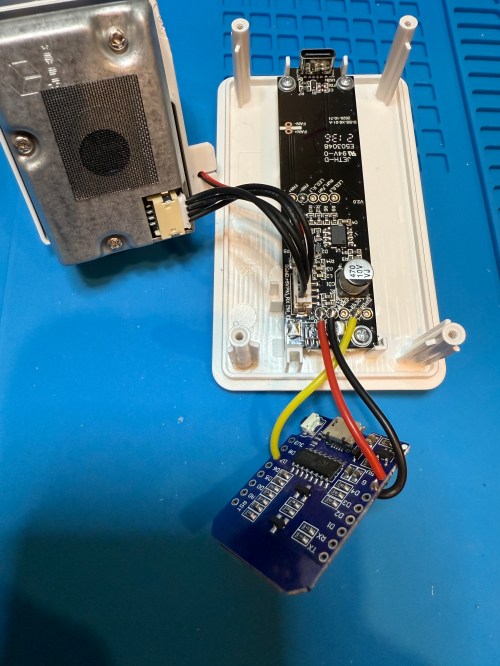

The final device lives right next to the waste bag dispenser I made. This way it’s easy to see the state and hit the button when cleaning out the litter. Here are photos in place with a few different states.

This project was so fun. Using Google Gemini for stuff like this makes it so much faster. I’ve had some of these microcontrollers and other parts for almost a decade so it’s nice to finally put them to use.

What other features or automations would you add to this? Have you built anything similar?