IKEA recently discontinued Vindriktning, their older air quality monitor.

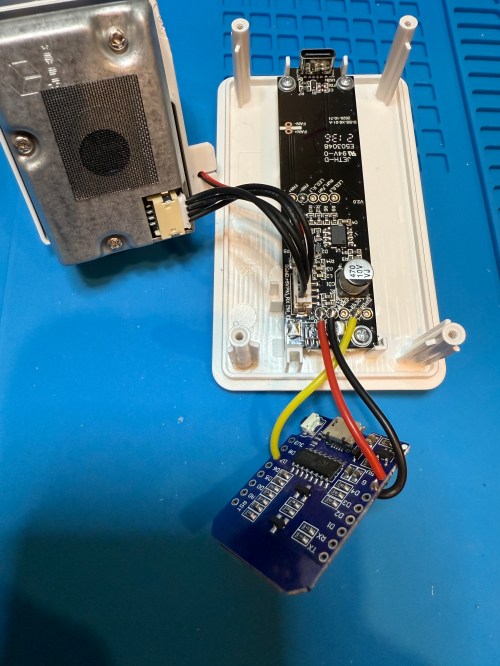

Inside the device, they put a cubic PM1006K particle sensor. I bought three for $16.95 each last year, because I’d seen people hack them by adding sensors and a Wi-Fi microcontroller to send all of the data to Home Assistant. For my modding I bought:

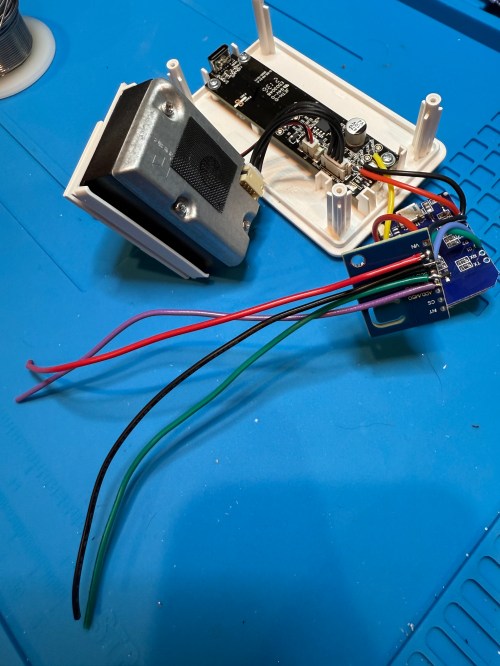

The YouTube video linked above is a great guide to follow. I didn’t connect wires to the fan or the light sensor since I had no use for them. I also didn’t stack my sensors because I wanted the BME280 to be outside of the enclosure, where it would be less affected by the heat produced by the ENS160 and D1.

Even with the sensor outside of the case, the BME280 still reads high, because it heats itself up. I actually tested different lengths of wires and placements of the sensor before realizing I was still going to have to adjust the data. An ESPHome filter made the adjustment easy, which I did individually for each unit after comparing to a mobile Ecobee thermostat sensor. This is the code from the unit for my shop.

substitutions:

slug: shop

friendly: Shop

esphome:

name: ${slug}-air-quality

friendly_name: ${friendly} Air Quality

esp8266:

board: d1_mini

logger:

level: WARN

api:

encryption:

key: 'xxx'

ota:

- platform: esphome

password: 'xxx'

wifi:

ssid: !secret wifi_ssid

password: !secret wifi_password

manual_ip:

static_ip: xxx

gateway: xxx

subnet: 255.255.255.0

i2c:

frequency: 100kHz

uart:

- rx_pin: D7

baud_rate: 9600

sensor:

- platform: pm1006

pm_2_5:

name: PM 2.5µm

- platform: bme280_i2c

address: 0x76

temperature:

name: Temperature

id: ${slug}_temp

filters:

- offset: -3.38

humidity:

name: Humidity

id: ${slug}_humid

filters:

- offset: 7.63

iir_filter: 16x

- platform: aht10

variant: AHT20

temperature:

name: AHT21 Temperature

id: ${slug}_aht21_temp

humidity:

name: AHT21 Humidity

id: ${slug}_aht21_humid

- platform: ens160_i2c

address: 0x53

eco2:

name: CO²

tvoc:

name: VOC

aqi:

id: ${slug}_aqi

name: AQI

compensation:

temperature: ${slug}_aht21_temp

humidity: ${slug}_aht21_humid

text_sensor:

- platform: template

name: AQI Rating

lambda: |-

switch ( (int) ( id( ${slug}_aqi ).state ) ) {

case 1: return {"Excellent"};

case 2: return {"Good"};

case 3: return {"Moderate"};

case 4: return {"Poor"};

case 5: return {"Unhealthy"};

default: return {"N/A"};

}

These resources were a huge help when I wired everything up and made changes to the YAML code:

- D1 Mini Pinout Reference

- IKEA-Air-Quality-Sensor on GitHub

- PM1006 Particulate Matter Sensor from ESPHome

- ESPHome: I²C Bus

- BME280 from ESPHome

- ENS160 from ESPHome

- AHT10 from ESPHome

Here is how I’m displaying the data on one of my Home Assistant dashboards.

As I was working on this project I knew I wanted a couple more air quality monitors around the house, which will be finished soon.

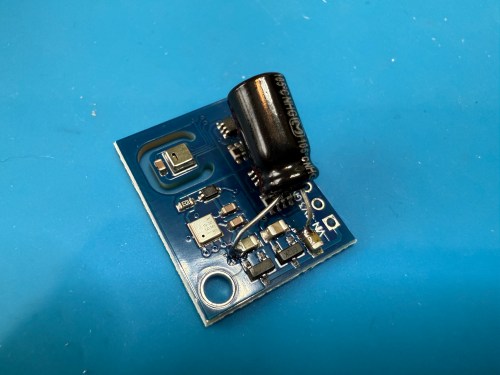

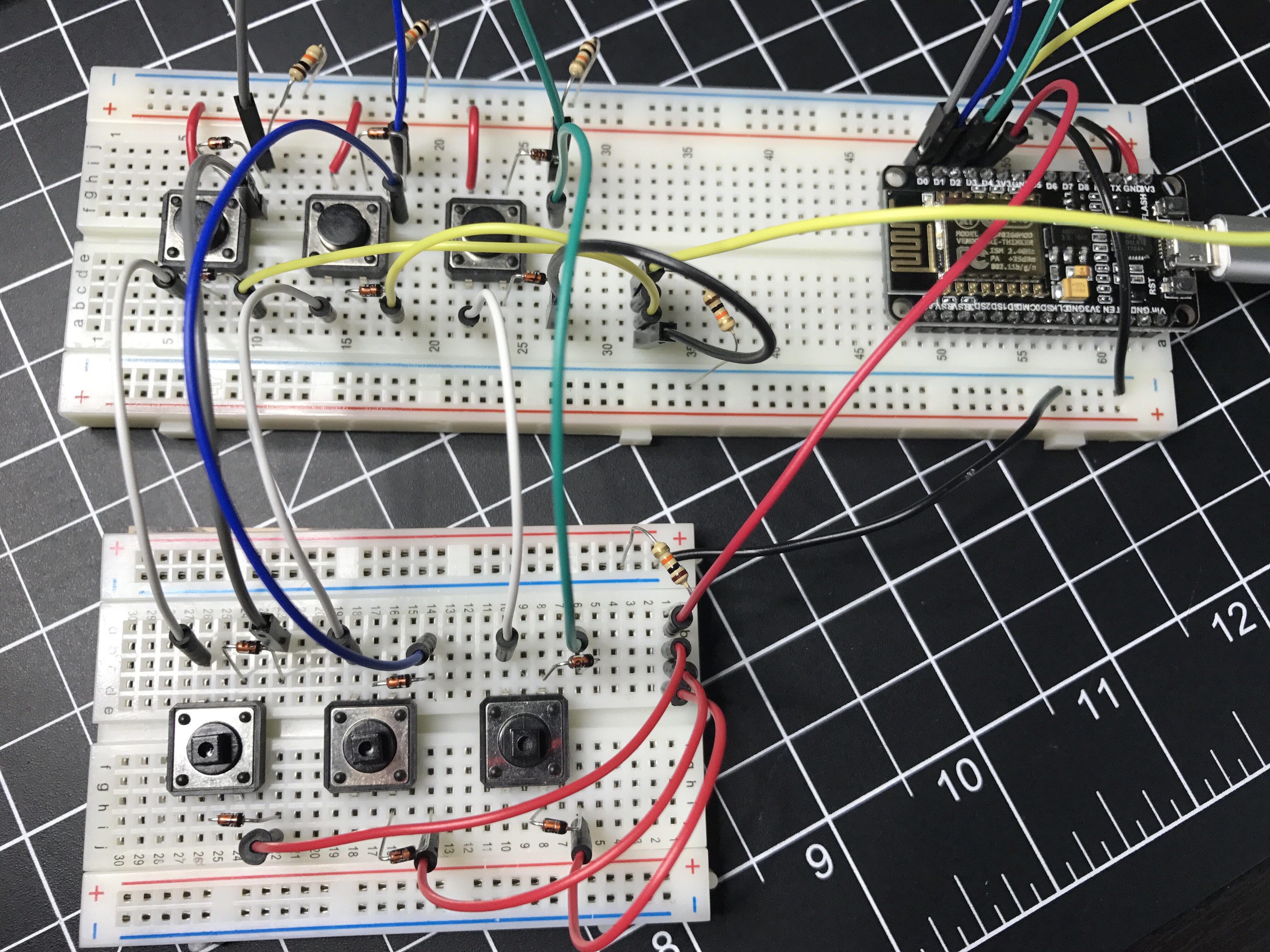

Update: I’ve had to make a small update by adding a 47uF capacitor to each ENS160 board, because they have power issues, causing the reading to stop for periods of time. My boards matched up with the right ones in the picture at that link. Here’s a picture of another ENS160 I modified, since it was a tight squeeze to made the modification on the devices I posted about here with everything already wired up. I also realized I was powering these through the 3V3 pin instead of VIN, so I fixed that.

I’ve also improved the display of the data on my dashboard by using mini-graph-card.

Early this year, I enjoyed watching

Early this year, I enjoyed watching  Pretty sure I’ve had this on my Kindle for at least 5 years, maybe even since it was released in October of 2011. After reading the Hardware Hacker and learning so much about electronics lately I felt it was a good time to dive in.

Pretty sure I’ve had this on my Kindle for at least 5 years, maybe even since it was released in October of 2011. After reading the Hardware Hacker and learning so much about electronics lately I felt it was a good time to dive in.

I’ve been on a kick tearing apart electronics. In addition to

I’ve been on a kick tearing apart electronics. In addition to

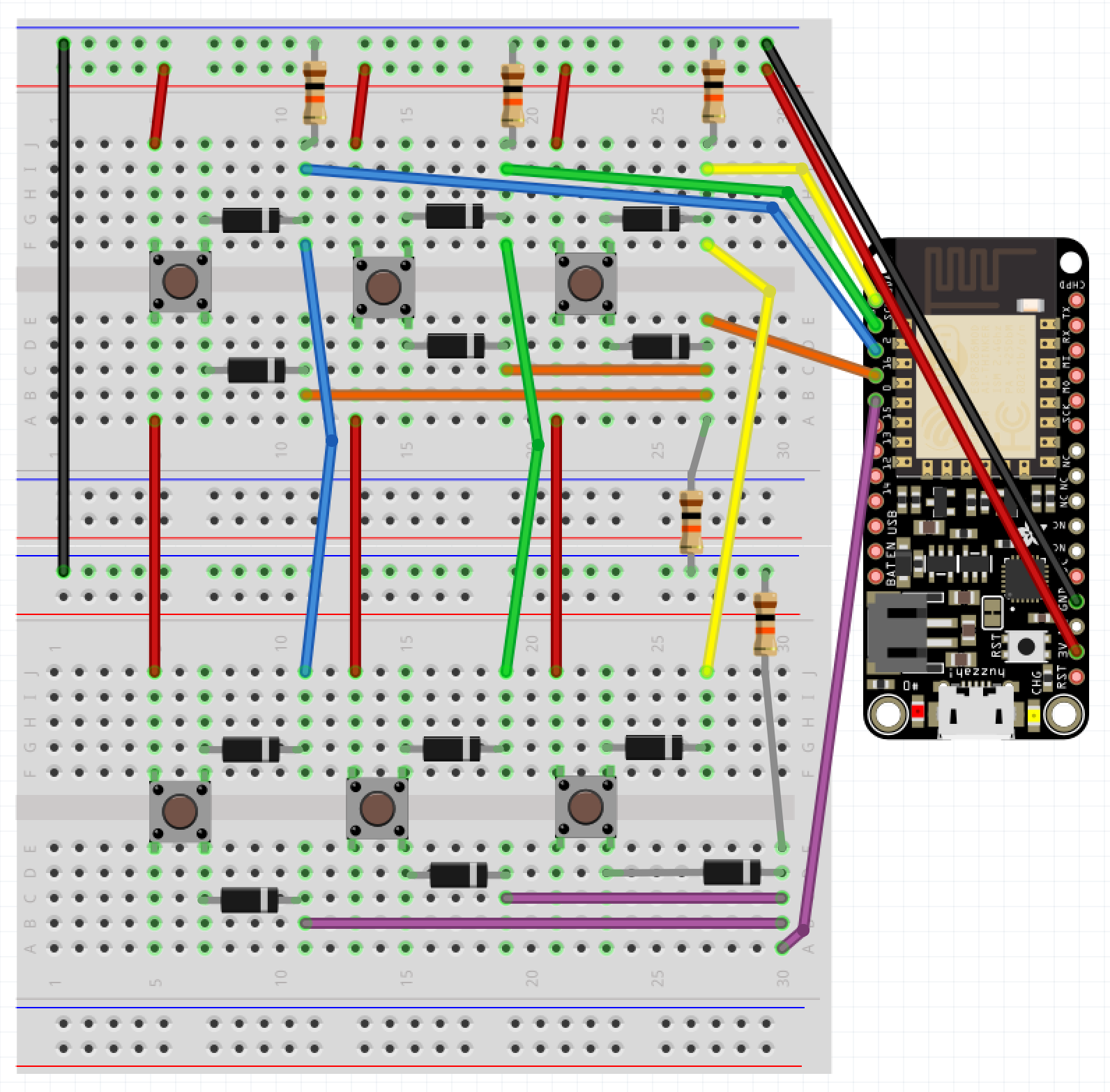

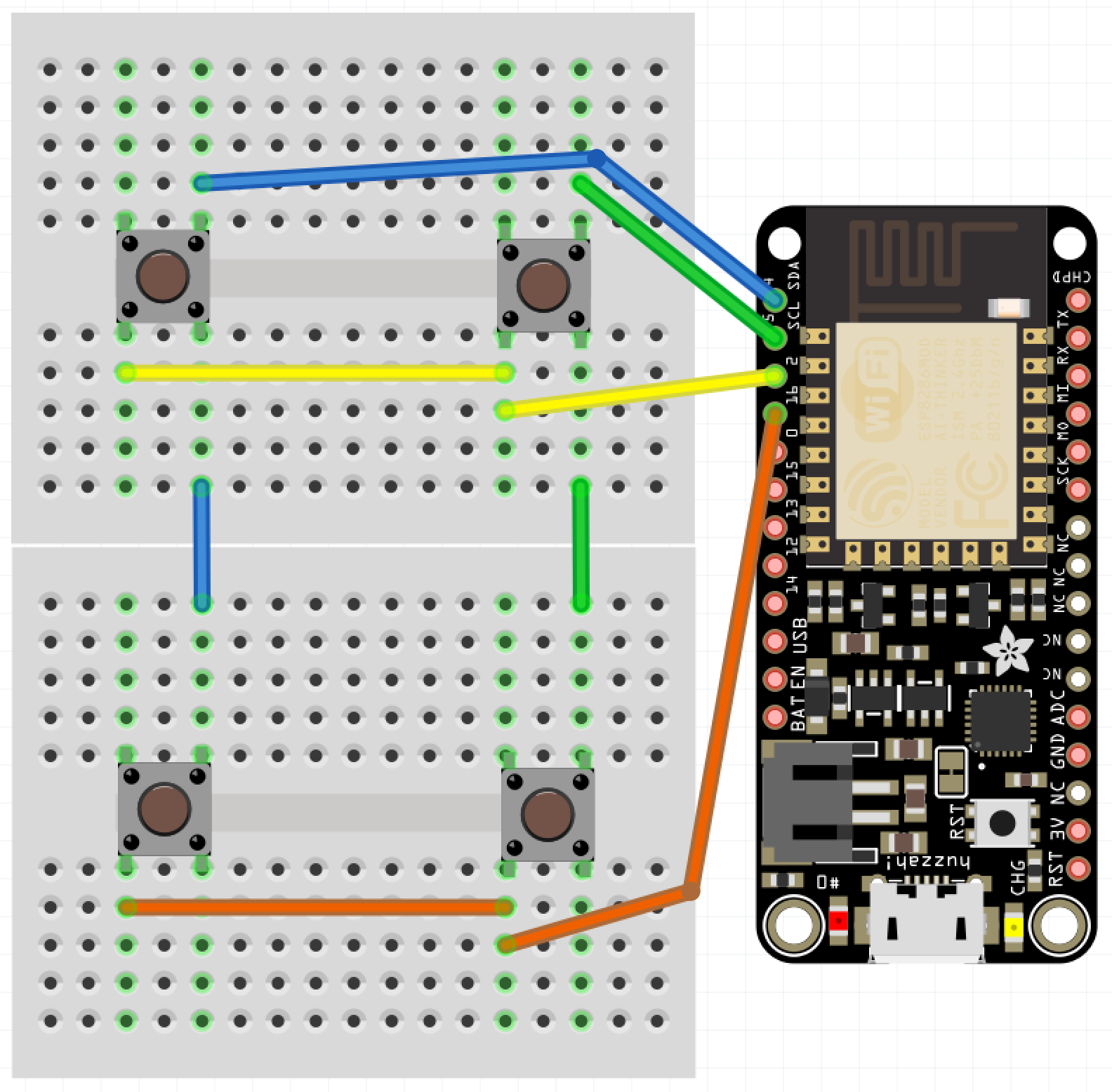

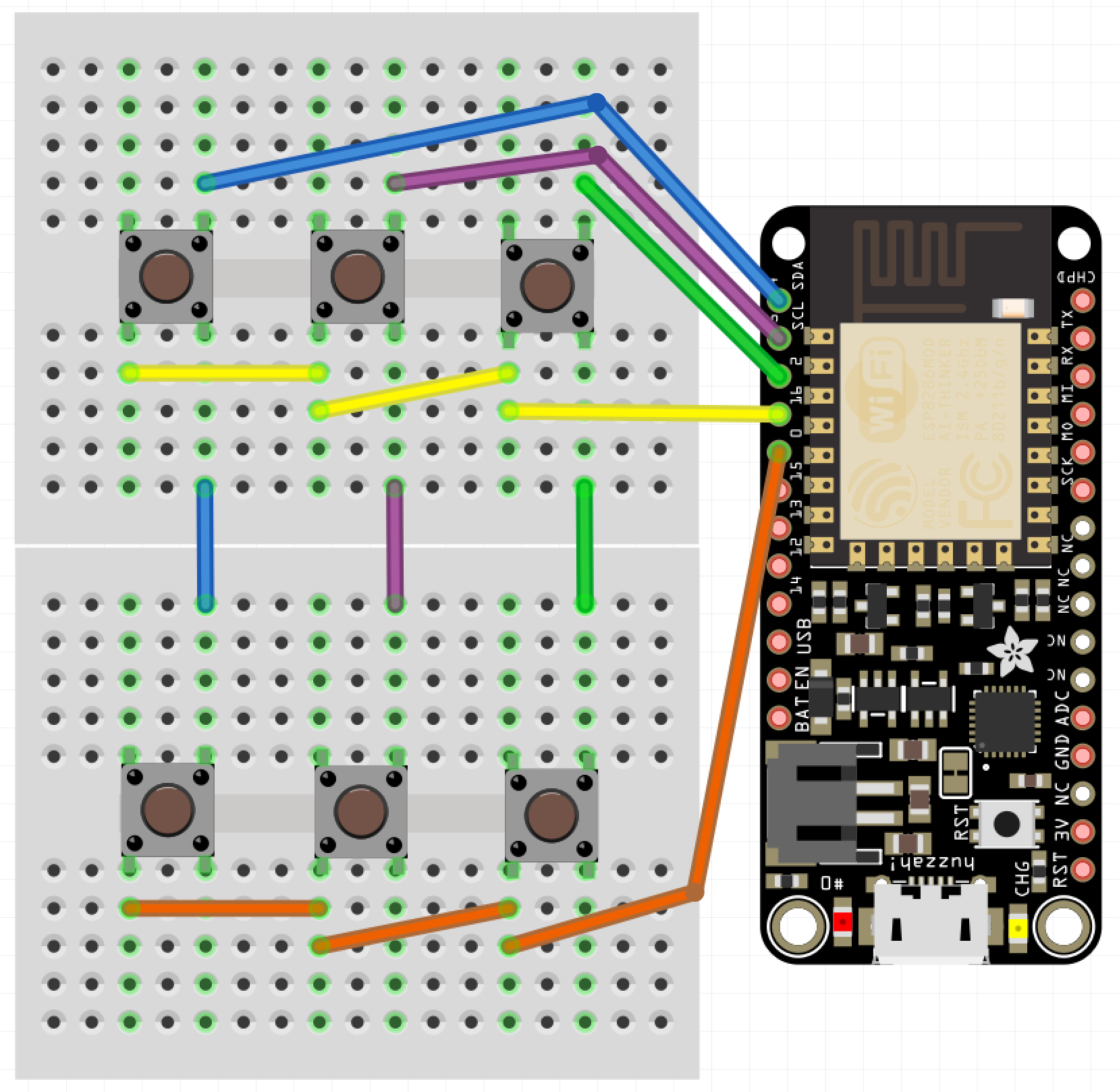

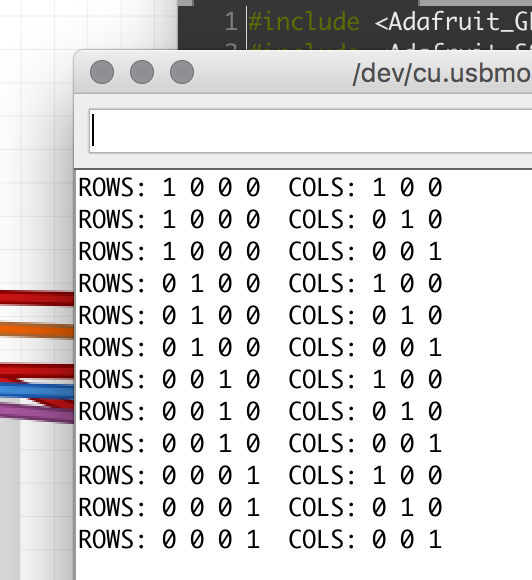

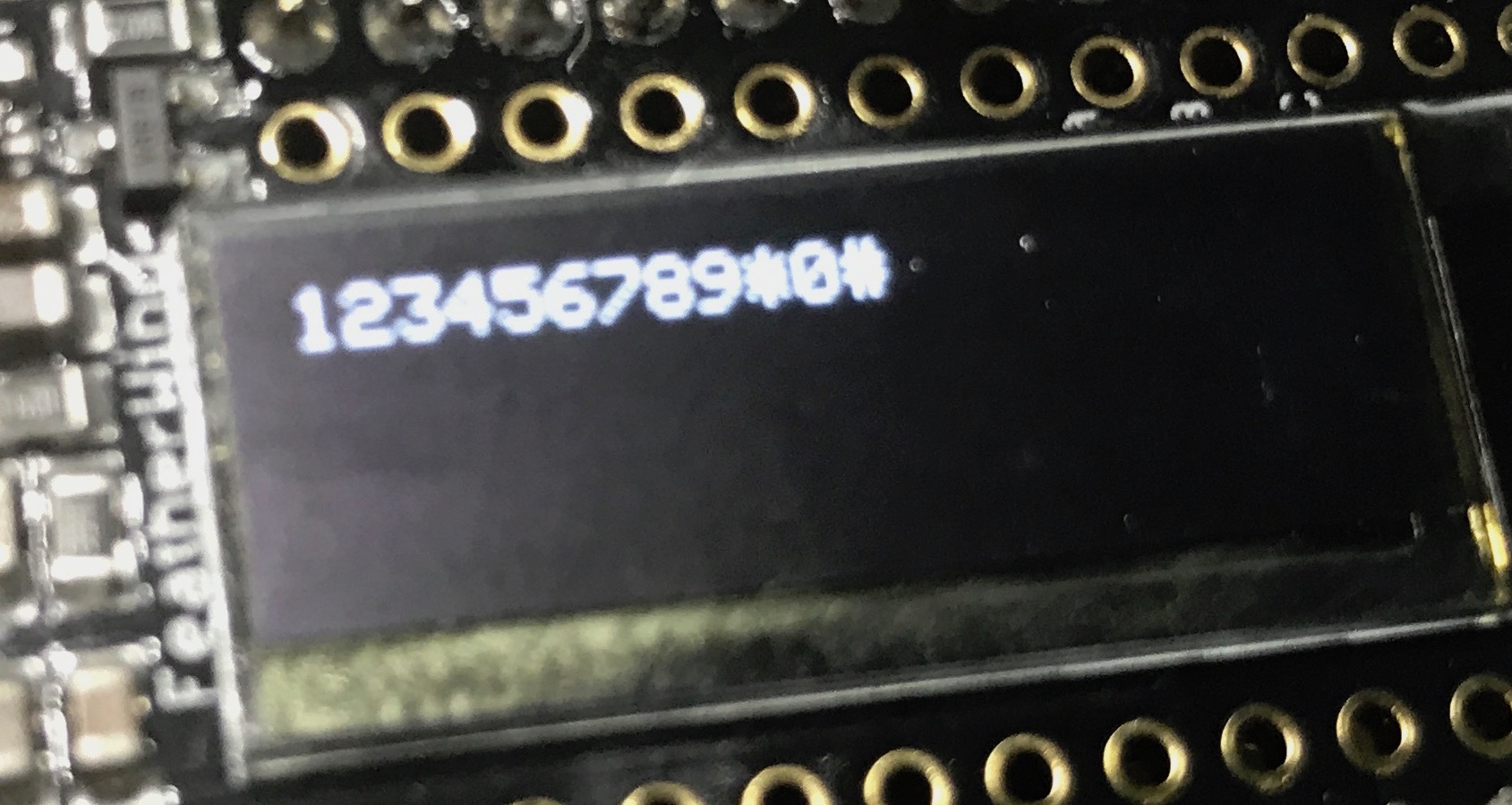

There are seven of them. The top has two and the bottom has one, which correspond to the 3 columns of keys on the grid. Then the left and right sides each have 2, which match up with the 4 rows of keys.

There are seven of them. The top has two and the bottom has one, which correspond to the 3 columns of keys on the grid. Then the left and right sides each have 2, which match up with the 4 rows of keys.