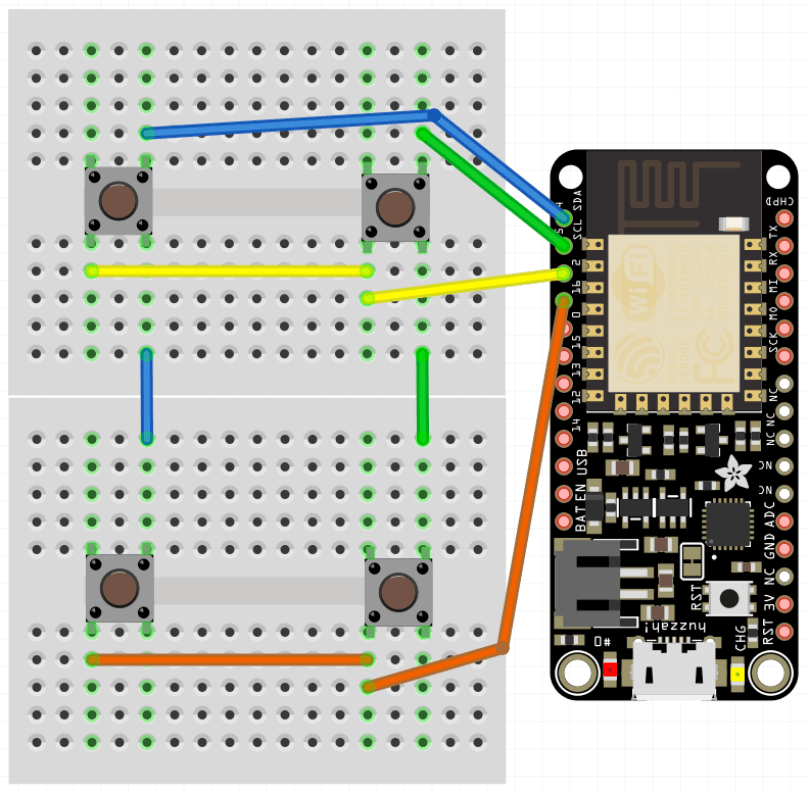

In parts 1 and 2, I walked through my journey of repurposing the keypad out of a phone from 1980. I learned that a more modern keypad matrix doesn’t exactly function (behind the scenes) in a way I’d expect. I wanted to understand it better so I set out to recreate a 2×2 keypad (kept it simple to make wiring easier) that would function the same way as something you can buy today. It would be a success if it worked with the Arduino Keypad Library.

From my earlier looks through the code I knew it pulsed power out to a column pin and then read in each row’s key from that column before switching to the next column and repeating the process. I figured that should be enough for me to wire this up and try example programs without going back to look at the library’s code again.

I don’t know why I was thinking this would be more complicated and at least a little more exciting, but it was unbelievably easy. I guess I should be celebrating I understood how it worked. Literally all you do is connect one side of every button in a column to a pin and one side of every button in a row to a pin. No need for connections to power, or ground. No pull up/down resistors.

It immediately worked with the Arduino Keypad library examples, even the MultiKey one. I guess being able to detect multiple key presses at once is where the advantage to this implementation comes in. It worked flawlessly when pressing 2 of the 4 buttons, but when you get to 3/4 there are too many connections to distinguish the keys.

Just to be sure I had it figured out, I added a 3rd column to make it a 2×3 grid and it was just as easy.

I love the beauty of how simple this is. I’ve added Fritzing for both of these to my phone-keypad GitHub repo (2×2 & 2×3). If you check this PDF, in the How it Works section it has a really good explanation and shows the row and column connections exactly like I came up with.

Naturally now I need to do a part 4 and attempt to recreate the keypad implementation I ended up with from the old phone. Due to how it mechanically makes the electrical connections I think it’s going to be a bit more complicated than this was. We shall see…

Update: Read part 4.

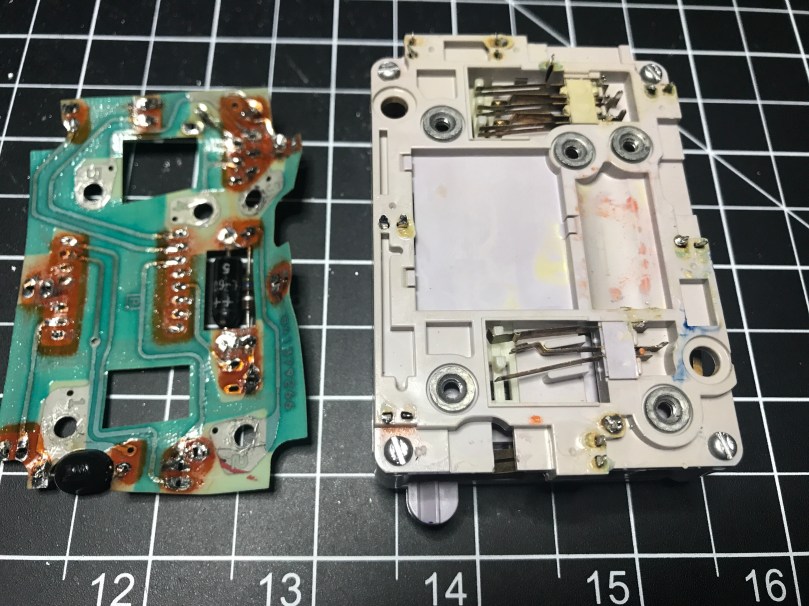

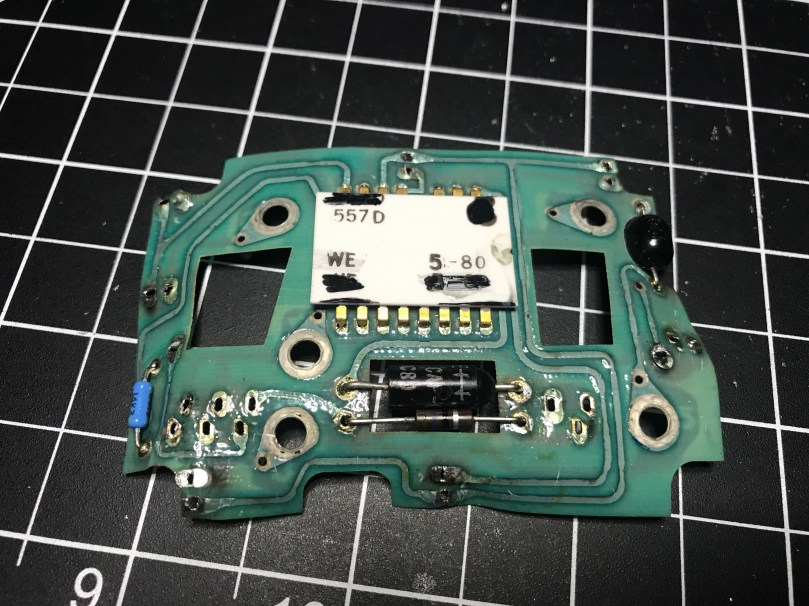

Go back and read Part 1 if you want to the full story on this little project. I did decide to get rid of the PCB on the old phone keypad. Good thing I’ve been getting a lot of desoldering practice. In order to remove the PCB, I first had to remove the wires I had added to the column and row contact points. That was easy and getting the PCB off was a pretty smooth process as well.

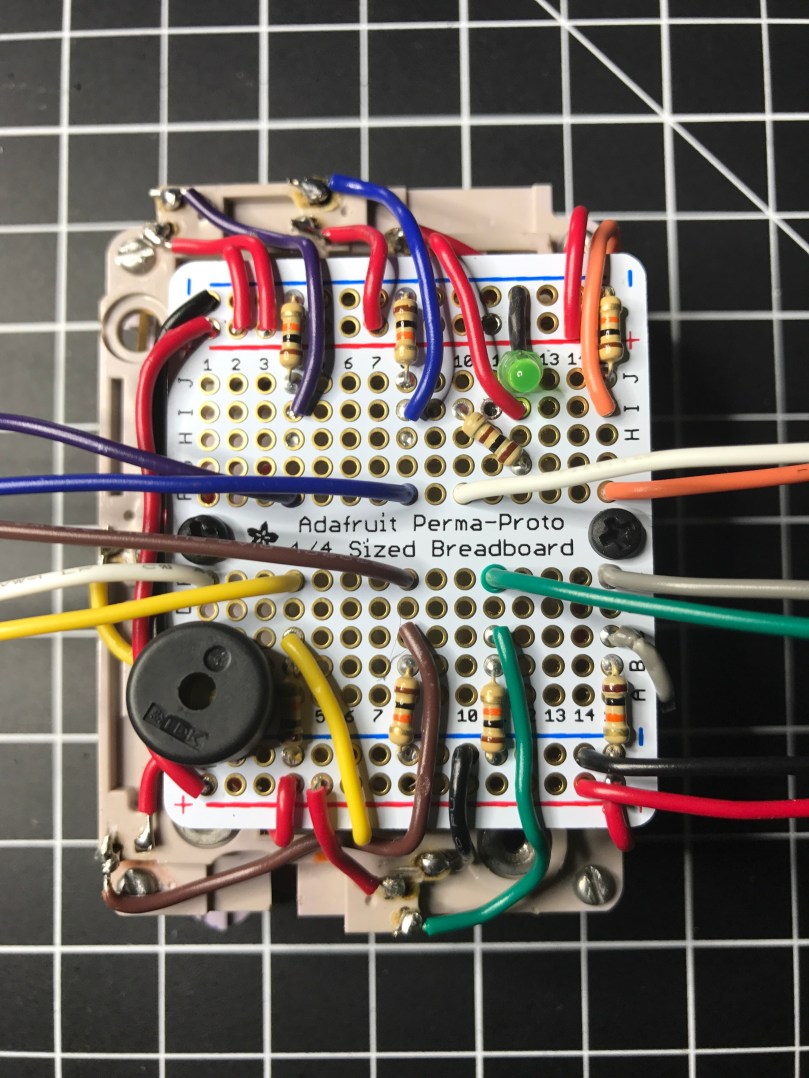

Now that I didn’t have the PCB to carry power and ground around everywhere, I had to solder in my own wires. I also had to solder back in all of my connection points to provide the outputs I’d feed into a microcontroller (I used an Adafruit Feather 32u4 Basic Proto).

Once all of the wires were in place and then connected to my microcontroller I wasn’t getting expected results from a simple little program I wrote to display the values. Took far too long for me to remember I needed to use pull down resistors to prevent floating values. I put 10k Ω resistors in each of the circuits…

Output from the pins couldn’t get any better…

I loaded an example from the Arduino KeyPad library, which gave me very weird behavior. After looking at the underlying code, I realized it wanted the outputs of the keypad to be HIGH when a key was not pressed and LOW when it was. Well, my circuit was doing the opposite, so I had to have to invert everything. I didn’t have any inverter ICs, so I used NPN transistors to create an inverter circuit on each output.

Progress. Now I was able to get the library to correctly recognize some key presses. 95% of the time it seemed to think everything was coming from column 1 (1, 4, 7, *) though. The library comes with a MultiKey example. When I ran that, it was reporting every key on the row as being pressed. WTF?!

For the life of me I could not figure out what caused this. I checked wires, measured voltages, did continuity tests, resoldered connections, changed boards, used different GPIO pins, and countless other things. Nothing made a difference. My own code was working beautifully though. Eventually I gave up on the library. It wasn’t worth the effort and I was out of ideas.

Update: Later on I went back and read the KeyPad library code again because it was bugging me. Turns out these keypads don’t actively read the column pins like they do the row pins. My assumptions about how they worked was very wrong because I hadn’t read far enough into the code before. When checking for key presses, typical keypads iterate through the columns to send a pulse which feeds over in to the rows, which are then read in. How a Key Matrix Works has a pretty good explanation with visuals. If I get my hands on another similar keypad maybe I’ll try to recreate this functionality.

I rewired everything to use the pull down resistors again (video of soldering). A huge benefit of the decision was it drastically simplified my circuitry. This would save me 49 solder points! I probably would have needed to use a half-size perma-proto board instead of the 1/4 size I ended up using.

I decided to put in a piezo buzzer to add sounds. I also used a tiny LED, which I had salvaged from some old computer speakers, to show when power is switched on to the backlight.

I tried a couple of different methods of producing touch tones (DTMF) to match up with each key, but with the microcontroller I’m using and the small piezo buzzer, the sound was terrible. I would need something a little more capable I think.

Here’s a demo video.

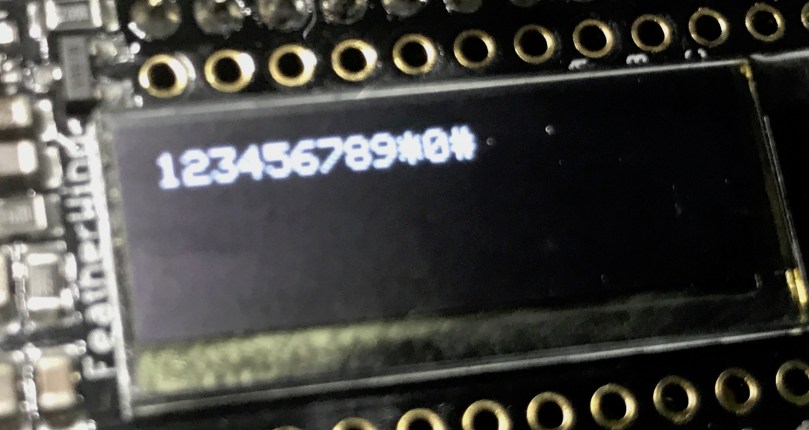

Hard to see the OLED screen in the video, but I was only using it to output each key press. Something like this…

All of the code and Fritzing wiring are available in my phone-keypad repo on GitHub.

I even went out of my comfort zone and did a quick share of this on Adafruit’s Show and Tell. If the video doesn’t start at the right spot you can skip ahead to the 12:42 mark. Going back to watch, my demo kind of sucked since it’s hard to hold something up to the Mac camera and push buttons at the same time.

Update: Continue on to Part 3, where I create a matrix of buttons to act as a keypad.

Even at 8x speed my soldering skills are still slow.

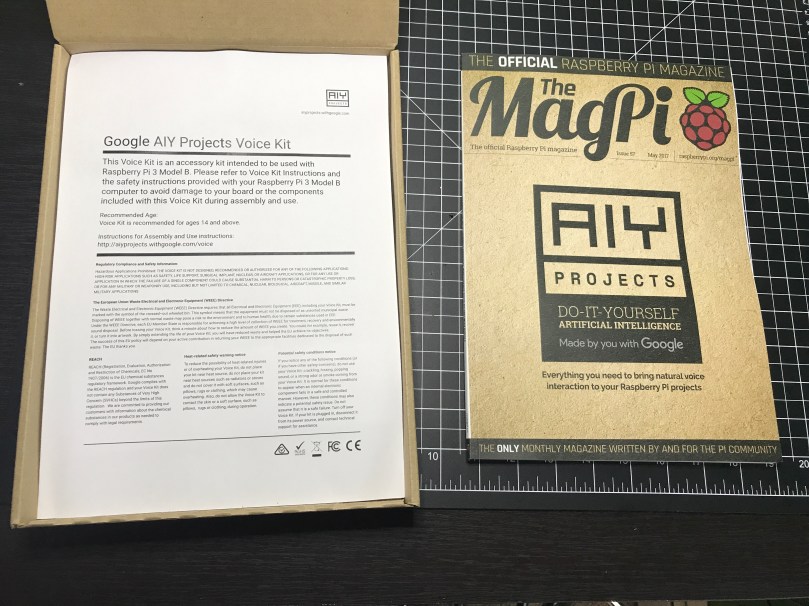

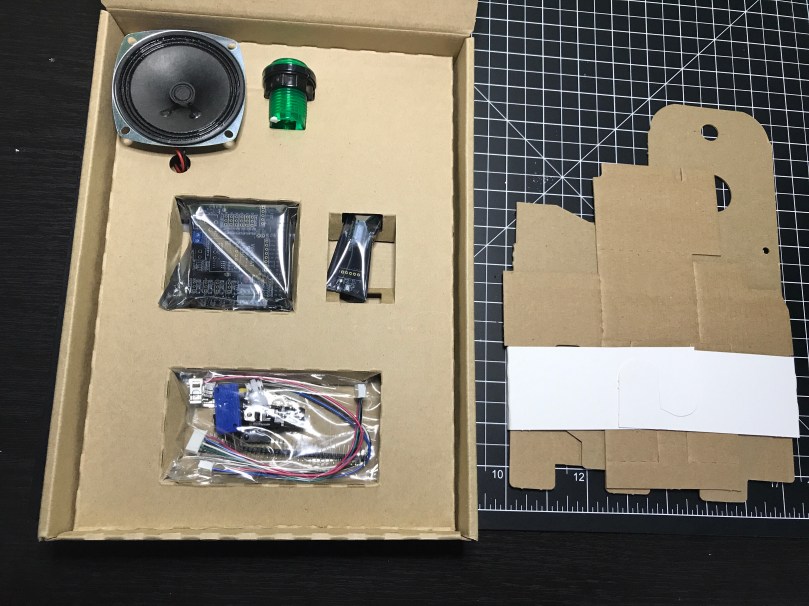

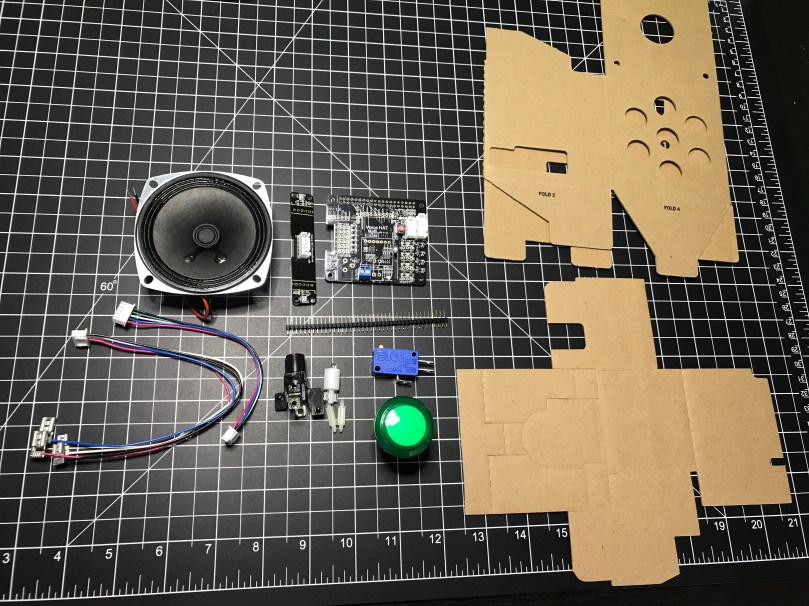

This morning when I saw the latest issue of The MagPi Magazine came with an exclusive Google kit, I wanted it. I was up early for a golf meeting and some errands so I stopped at Barnes & Noble to see if they had any copies. I was excited to find a couple on the shelf!

The woman working the register said she had just put them out and there was actually a 3rd copy that was coming apart so she was going to glue it back together.

At $15 for a magazine, I don’t think you can really call this a “free” kit, but it’s still a good value. I don’t think I’ve ever “unboxed” a magazine before…

This will be neat to mess around with. I’ve thought about turning one of my Pis into an Alexa type device to put in my office or bedroom and could easily do it now. If you have any project ideas involving voice, let me know.

Electronics Engineering ToolKit is a useful iOS app if you’re messing around with electronics. I think I paid $6.99 to upgrade to Pro, which unlocks all of the formulas, reference material, and tools.

I recently posted Using a 555 Integrated Circuit. There are many ways to use these 555s. To get a sense of the power of this app, it has 10 tools in its 555 Timer IC group! Here’s a look at the Monostable operation mode. Each tool in the app has a great info panel like this one, describing what it does.

The tool itself gives 2 inputs where you set your resistor and capacitor values and it calculates the time for you.

It provides a circuit schematic where the R (resistor) & C (capacitor) values are updated instantly, based on you input values. This schematic doubles as a simulation, where it really gets cool. You can tap on the button to see how the circuit reacts. In this case, the LED turns green (ON) for 2.42 seconds and then turns off.

I wired up the circuit to try it for myself. Worked exactly as expected. I even triggered my live circuit and the simulation at the same time and the LEDs turned off simultaneously.

This is just one example of many useful things you can do in the Electronics Engineering ToolKit app, especially with the Pro upgrade. Not only can you favorite (as shown at the beginning of this post) the tools you find most useful, but the app also has a great search feature.

You can find similar tools for specific formulas and uses around the Internet, but I haven’t come across anything where it’s all in one place with an easy to use interface like this. Perhaps the best web site I’ve found is Basic Electronics Tutorials and Revision, which is a bit higher level in the way their descriptions.

I’ve been on a kick tearing apart electronics. In addition to the switch I got a bunch of parts from, I’ve tore into a lamp and some old computer speakers. When I found an old telephone (it has a date of 5/30/1980 printed on it!) in my basement I knew I had to see what was inside. The previous owners left it in a storage room and I have no idea why I never pitched it. I didn’t take a picture before taking a screwdriver to it, but it looked exactly like the photo on the right.

I’ve been on a kick tearing apart electronics. In addition to the switch I got a bunch of parts from, I’ve tore into a lamp and some old computer speakers. When I found an old telephone (it has a date of 5/30/1980 printed on it!) in my basement I knew I had to see what was inside. The previous owners left it in a storage room and I have no idea why I never pitched it. I didn’t take a picture before taking a screwdriver to it, but it looked exactly like the photo on the right.

People have been hacking phones for a long time. Perhaps the earliest and most well-known was the Steves (Jobs and Wozniak) using a blue box on payphones. I’m nowhere near that level, but you have to start somewhere right? I pulled the ringer, speaker, and microphone out of it. I haven’t messed with these yet.

The part I thought would be neat to work with was this keypad.

It was a bit of a process figuring out how to tap into this thing. Eventually I realized what these contact switches on the sides were for.

There are seven of them. The top has two and the bottom has one, which correspond to the 3 columns of keys on the grid. Then the left and right sides each have 2, which match up with the 4 rows of keys.

There are seven of them. The top has two and the bottom has one, which correspond to the 3 columns of keys on the grid. Then the left and right sides each have 2, which match up with the 4 rows of keys.

This row/column grid system is still how we reference the individual keys on keypads like this. Arduino has a Keypad library for working with modern keypads like one sold by Adafruit.

I figured out I could solder wires to the contacts points connected to each of those switches. I was in! From the way the keypad was connected to the rest of the phones circuitry I knew the screws were an important piece to tie it all back into the entire system. After some trial and error I determined which screws should be used for power (red wire) and ground (black) in order to get useable data out of the 7 switch contact points. The other 3 screws also connect to power. I was using alligator clips on those, but disconnected them for the picture.

Something isn’t quite right about the screw connections though. When I connect them the opposite way, flopping to have 1 power and 4 grounds, the backlight on the keypad works, but the readings from the soldered contact points are useless. With them connected this way, I don’t get the backlight, but I get data I can make sense of. There is probably something obvious I’m missing about how this all works together.

Unfortunately for me, the output from the contact points isn’t digital (limited to on/off), so I couldn’t use the Arduino library. It would have made things so much easier. It’s not surprising though, since this piece of technology is almost 40 years old!

I was able to get some code mostly working. Detecting the column of a button press was pretty straight forward and works great. Rows detection is another story. I’m reading in analog values and using sampling along with standard deviations to determine which row’s value is unlike the others. Well, the first row always reads a pretty high value, when a key on any row is pressed. The values for the other rows fluctuate as expected. When that first row is high, I’ve attempted to also look for a high value from another row, but it triggers the wrong row too often.

Demo time…

Even making this short little video, which took at least 5 takes, there was a false trigger for pressing 1 and many key presses not being recognized. Not useable.

I have a hunch the screw connections are responsible, at least in some part, for sending DTMF signals, also known as Touch-Tone. I don’t really care to get in the business of decoding these. This is precisely why I was hoping I could detect useful output from each of the row and column contact points.

I pulled apart the unit even more and discovered a Western Electric 557D is the brains of the operation, but it’s so old there doesn’t seem to be a datasheet online for it. What I’m going to do is remove the PCB and wire up everything on my own. Then I can easily get on/off as digital values from the columns and rows and make sure the backlight works. Stay tuned…

Update: Read Part 2

The battery (CR2450) in my garage door sensor was getting low, so I replaced it. I’ll keep the old one in my electronics kit for LED testing, as shown in this video. Touch the longer leg (anode) of the LED to + and the shorter leg (cathode) to –. Usually + is the top of the battery where the words are. Don’t worry, you won’t hurt the LED if you connect it the wrong way.

Remember last week’s post about tearing apart a component switch to repurpose parts? I spent some time fooling around with IR after that. I thought it would be neat to recreate the basic functionality of switching between 3 devices. For my proof of concept the devices were simple the 3 status LEDs, but you can imagine the possibilities of turning on different devices or triggering processes run on a computer.

The new microcontroller I got is one I posted about a few months ago, called Puck.js. It has an IR transmitter built-in, so I wanted to use it to mimic a remote. Puck.js is pretty slick. It’s really neat being able to program a device in Javascript through a web IDE over Bluetooth Low Energy. No wires at all!

Here’s a video of my hacking results.

Time for the geeky stuff…

First I tried recording IR commands from the remote using the method shown in the Infrared Record and Playback with Puck.js tutorial. I ran into two problems.

My next thought was to wire up to one of my other microcontroller that run Arduino, but the popular IR Library (IRLib2) doesn’t support the chips used in any of the boards I have. So over to a Raspberry Pi Zero. Pretty much every search result mentioned using Linux Infrared Remote Control (LIRC). May of the setup instructions I found were incomplete, but I was able to get things running by taking pieces from these two sites:

I’ll detail the steps that worked for me. Before I go down the software route though, I wanted to make sure the IR sensor worked. The only markings on the component are “71M4” and I have been unable to find a datasheet anywhere to match. Luckily these IR receivers are pretty standard and I had a pretty good idea of the pins from looking at how it was connected in the old device.  I got the idea of hooking up a simple LED test circuit on the data pin from an Adafruit learn guide. Pin 1 is data, going into a GPIO pin on the Raspberry Pi (26 in my case), pin 2 is ground, and pin 3 is power (VCC). You may want to use the 3.3V pin on the Pi to provide your power instead of 5V just to be safe, or consult the datasheet for the IR sensor you’re using. Connect the anode of the LED to power and the cathode to pin 1 of the sensor using a 220 Ω (I used 200) resistor. When you press buttons on an IR remote, the sensor will send data through pin 1 and the LED will light up. Here’s a Fritzing wiring diagram for this test as well.

I got the idea of hooking up a simple LED test circuit on the data pin from an Adafruit learn guide. Pin 1 is data, going into a GPIO pin on the Raspberry Pi (26 in my case), pin 2 is ground, and pin 3 is power (VCC). You may want to use the 3.3V pin on the Pi to provide your power instead of 5V just to be safe, or consult the datasheet for the IR sensor you’re using. Connect the anode of the LED to power and the cathode to pin 1 of the sensor using a 220 Ω (I used 200) resistor. When you press buttons on an IR remote, the sensor will send data through pin 1 and the LED will light up. Here’s a Fritzing wiring diagram for this test as well.

My test was successful! Now I was able to move on with some confidence knowing the part worked.

Install LIRC:

sudo apt-get update sudo apt-get install lirc

Edit the /etc/modules file:

sudo nano /etc/modules

Add to the end:

lirc_dev lirc_rpi gpio_in_pin=26

Change the pin if you’re using something other than 26. If you’re also going to do IR transmitting, you can add a space and gpio_in_pin=22 on that last line.

Press Ctrl + X, hit Y to say you want to save, and then Enter.

Edit the /etc/lirc/hardware.conf file:

sudo nano /etc/lirc/hardware.conf

Look for the DRIVER, DEVICE, and MODULES settings. Set them to match:

DRIVER="default" DEVICE="/dev/lirc0" MODULES="lirc_rpi"

Press Ctrl + X, hit Y to say you want to save, and then Enter.

Edit your /boot/config.txt file:

sudo nano /boot/config.txt

Look for this line:

# Uncomment this to enable the lirc-rpi module

If you see it, remove the # from the next line and edit it to look like this (if your file doesn’t have it, add this to the end of the file):

dtoverlay=lirc-rpi,gpio_in_pin=26

If you’re going to do transmitting, also add this to the same line:

,gpio_out_pin=22

Change both pins to match whatever you’re using. Press Ctrl + X, hit Y to say you want to save, and then Enter.

Reboot your Pi:

sudo reboot

Now it’s time to use LIRC to record the codes sent by whatever remote you’re using. First you’ll want to see names you want to give your buttons. Run:

irrecord --list-namespace

Scroll through the list and make notes on all of the codes you want to use for your buttons. You’ll need the codes in a bit. Here was my list:

KEY_POWER KEY_1 KEY_2 KEY_3

Stop LIRC:

sudo /etc/init.d/lirc stop

Use irrecord to create a configuration file for your remote. Follow the instructions carefully that come up on your screen. This took me several minutes for my remote with only 4 buttons.

Note: When it says Please enter the name for the next button (press to finish recording) is when you’ll need those codes above.

irrecord -d /dev/lirc0 ~/lircd.conf

When finished you’ll have a new file in your home directory. Take a look at it:

cat ~/lircd.conf

Mine looked like:

begin remote

name /home/pi/lircd.conf

bits 16

flags SPACE_ENC|CONST_LENGTH

eps 30

aeps 100

header 9004 4474

one 580 1666

zero 580 542

ptrail 578

repeat 9006 2229

pre_data_bits 16

pre_data 0x61D6

gap 107888

toggle_bit_mask 0x0

begin codes

KEY_POWER 0x7887

KEY_1 0x40BF

KEY_2 0x609F

KEY_3 0x10EF

end codes

end remote

Make a backup of the default LIRC configuration file:

sudo mv /etc/lirc/lircd.conf /etc/lirc/lircd_original.conf

Move your new configuration file over:

sudo cp ~/lircd.conf /etc/lirc/lircd.conf

Restart LIRC:

sudo /etc/init.d/lirc start

Install the Python LIRC library:

sudo apt-get install python-pylirc

Create a pylirc.conf file:

nano pylic.conf

You need to set up each button similar to what mine looks like:

begin remote = * button = KEY_POWER prog = pylirc config = KEY_POWER end begin remote = * button = KEY_1 prog = pylirc config = KEY_1 end begin remote = * button = KEY_2 prog = pylirc config = KEY_2 end begin remote = * button = KEY_3 prog = pylirc config = KEY_3 end

Do a simple copy/paste and change the button and config for each entry.

Press Ctrl + X, hit Y to say you want to save, and then Enter.

Create a basic Python test program:

nano pylirc-test.py

Paste in:

#!/usr/bin/python import pylirc pylirc.init( 'pylirc', './pylirc.conf', 0 ) while ( True ) : s = pylirc.nextcode( 1 ) command = None if ( s ) : for ( code ) in s : print( code["config"] )

Press Ctrl + X, hit Y to say you want to save, and then Enter.

Run the program:

python pylirc-test.py

Press buttons on your remote and if everything is working you’ll see the special name codes being output for each button you press.

Hit Ctrl + C to stop the program.

I already had all of the logic written for the buttons to work and switch LEDs, so it was easy to add in a little more code to take action when the appropriate IR codes were received.

Once I found the correct information, setup on the Pi was quite easy. A lot of steps, but easy stuff. Making the Puck.js duplicate my Infrared remote’s codes was a bit of a challenge. From the Puck.js Infrared tutorial I linked at the beginning I knew I needed to have an array of pulse lengths, but I didn’t have anything like that from the LIRC configuration. All I had was some hex values for each code:

Combined with another hex code for pre_data (0x61D6) from the lircd.conf file, I had more complete codes:

I searched all over for tools to reverse these into pulses or “Pronto Hex” values, which I also found could be used with Puck.js by decoding them. I couldn’t find anything. At some point I came across the Infrared remote control signals repository on GitHub.

Infrared remote control signals from the LIRC remote configurations project, converted to Pronto Hex and Protocol, Device, Subdevice, and Function using lirc2xml…

BINGO! It had the Pronto Hex codes. I cloned the repo and started searching for my hex values. I found power, 1, and 2 matched up with codes used by something called a gigabyte TV. I plugged the codes into a program and they worked! I was only missed the code for button 3.

Then I spend way too much time still searching around. I knew enough about how IR worked and had 3 codes. I finally realized I should be able to figure out what changes to make in order to get my 4th and final code. I converted the hex values to binary:

Then I started looking at the end of each array of Pronto Hex codes, because every code uses the same pre_data. I quickly determined an ON bit (1) was 003e, OFF (0) was 0013, and they were separated by 0017. I made the necessary adjustments and had all 4 buttons working with IR!

This IR journey turned out to be quite an adventure. I learned a lot, which was the point. My infrared-3-input-selector project on GitHub has the Python program used in the demo video, my pylirc config file, the simple pylinc test program, the Puck.js code, and even an Arduino sketch with the button and LED logic I created initially before realizing I needed to switch to the Raspberry Pi.

Adafruit has a cool iOS game, named Mho’s Resistance, to help teach you how to read resistor codes.